On McCracken on Malick

I said I liked this review by Brett McCracken of the new Terrence Malick film “Knight of Cups” and my friend, the artist David Wittig, asked why, so I thought I’d try to figure it out.

I said I liked this review by Brett McCracken of the new Terrence Malick film “Knight of Cups” and my friend, the artist David Wittig, asked why, so I thought I’d try to figure it out.

First though, I should mention that I haven’t seen the film, so I can’t say whether McCracken’s is a good review of Knight of Cups, only that I appreciate it as a film review, and as a piece of writing. It may well be that the disconnect between McCracken’s reading and the actual film is so great that it’s a terrible review of the film, but I wouldn’t know.

Second, I should say that I pretty much hate movies. I just don’t appreciate the genre as entertainment, let alone as art, which brings me to the first thing I like about the CT review: it gives me permission to skip this film. I skip most films, of course (see aforementioned hatred) but when a new Malick film comes out, I feel compelled, like I should see it somehow, like it’s part of an artistic person’s duty. So I probably would have seen this, or at least felt bad about not seeing it. But I don’t now, because of this piece. I think this happens because you can tell, reading it, that McCracken wants to like the film. He’s not dismissive like many reviewers are, nor a booster, nor so vague one can’t tell where he stands on it, providing mere description and letting we wizened readers decide ourselves. Rather, he enters the viewing with generosity of spirit and a good deal of background and comes out of it demurring.

That’s kind of amazing because McCracken is the biggest fanboy I know. He loves Malick films like few people love anything. It’s basically the only thing I know about him, apart from the fact that he routinely attacks people from my tribe (hipster/Christians) and that he somehow thinks the latter Coldplay albums as good as the first two, an error of judgement so profound I stopped following his twitter. But even given that fandom, he walks away from this film shaking his head.

I recognize that gesture, which is another thing I appreciate about the review. Like many, I admired Tree of Life for its patience, dedication to beauty, and willingness to stare into the maw of grief without melodrama. But when I saw the next one, To the Wonder, I found it precious, bored, and self-indulgent. Part of the problem was casting Ben Affleck, which one does not do if one wants to make a serious film, and part was Malick’s misunderstanding, and then minimizing, the best parts of his own story. He thought it was about the beauty in mundanity, how the bare American landscape and its attendant suburban culture are redemptive despite their tawdriness, but really it was about the spark in the priest character and that visiting French woman that wasn’t extinguished somehow (because they were not Americans? Because they believed in something older than oilfields?). In that, I think of Malick like John Berger thinks of Picasso: that he’s insanely talented, and has failed to find a subject worthy of his attention.

He doesn’t come out and say it, but I take McCracken to be accusing Malick of committing the mimetic fallacy: of making a film that ostensibly criticizes the vacuous pretty-people lifestyle of Hollywood by making vacuous, pretty images of those things. Viewers, I take it, leave the film feeling empty and slightly dirty, and that is, I take it, the point. And I could so see Malick doing that. With his slow camera work, distrust of traditional narrative structure, and an idolater’s devotion to female physical beauty, he’s ideally poised to make that sort of film. If so, I disapprove. Having watched Mad Men, I’m exhausted of the self-indulgent posture that at once criticizes and enjoys the representation of titillation. I mean, pick a team, and put on the jersey already.

I’m inclined to think McCracken is right about this aspect of the film (though he may not be; again, I haven’t seen it) because I know from those previous films that Malick (like many artists, especially ones who work in commercial media) loves a shortcut. For all his 1000 hour film schedules, and all his auteur rebellion, he does tend to rely on the occasional gimmick to get the job done, reducing complex theology to a binary between law and grace, for example, or the hard work of love to some feeling that can be “over” according to mood or a hard winter. I can just see him using bits of Debussy to nod toward, but never actually engage, another world of meaning. He’s the kind of director who just drops in Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” whenever the mood strikes, rather than earning it, honoring it. So he may use the beauty of Natalie Portman’s face, or the beach/sunset in just the same way: shortcuts to the heart without the proper tillage. As Monty Python says, “Stimulating the clitoris? What’s wrong with a kiss, boy?”

Finally, I feel taught, strengthened by McCracken’s review in the way Malick probably means his audience to be. When McCracken suggests that “any pilgrim” needs “rehabilitation of the senses” through “a more attentive posture in the world” I feel that I have, in a sentence, all the film can give me, and a bit more because I can work the koan into my life. That’s something I believe deeply, and something —again, this is weird—that McCracken actually practices in the review. Rather than fire off some thoughts, as I’m inclined to do, or as his colleagues do by fiat and culture, he stews. How much better if reviewers said “I don’t know what to make of this film. I waited for a week before writing anything about it. I talked it over with my wife.” I like the struggle of it, I guess, rather than the usual critic’s posture of sitting above the fray dispensing judgments.

On the level of style, I also appreciate McCracken’s statements about postures of openness as rebellions against framed realities, and the double entendres on “Sunset Strip” and “Paradise Lost.” And my goodness, the idea that a kind of gaze could act as a bulwark against the tendency to “turn pretty things into porn,” which who among us hasn’t felt, and which Stephen Dobyns gets at, at least as successfully, in this poem.

Maybe I’ll see the film and maybe I’ll change my mind. But in the meantime, I’m glad I read this, and even if it turns out he’s wrong about everything, I’ll still be glad to have thought about it with him.

Ronson Review

I read this book by Jon Ronson because Austin Kleon told me to, and I basically do whatever he says.

I read this book by Jon Ronson because Austin Kleon told me to, and I basically do whatever he says. It’s an account of how we use social media to shame others into normality and it’s written in investigative journalism prose with the an added lift at the end of every section that links to the next in the manner of Buzzfeed *click for more* previews. Ronson is a likable sort, though a bit gregarious in his support of The Fallen; their “suffering” is rendered as the very nadir of human travails, though several of his examples are still very rich and popular. I keep thinking about ditching social media altogether, since it brings much more anger and anxiety into my life than it does joy or peace and this book shoved me a little more in that direction, but though Ronson means it as a meditation on where we are now, it’s more like reading a mystery than anything else. I agree that shame can be paralyzing, and that the punishments a hostile public meets out are often unjust. But–perhaps it’s just me–the accounts of the various rises and falls in this book felt, firstly, salacious, and secondly, concerned as they were with pop-cultural figures and other ephemera, rather too of the moment: very cool as magazine articles, but hardly meaty enough for a book. I don’t know. It was fine.

Eugenia Leigh "Psalm 107"

Here’s a little prayer by Eugenia Leigh that I found on the Poetry Society of America Website.

Here’s a little prayer by Eugenia Leigh that I found on the Poetry Society of America Website.

-(Poems for the People)

Romanticism Pitch

I was thinking of a special topics class I could offer for graduating seniors in the in English Department here at Northwest University, and came up with the following, for which I mocked up this poster design.

I was thinking of a special topics class I could offer for graduating seniors in the in English Department here at Northwest University, and came up with the following, for which I mocked up this poster design.

My department chair, sensible fellow that he is, responded that my poster might, around this relatively conservative place, “raise unwarranted suspicion,” suggesting instead that I pitch a design that’s “dramatically benign.” I countered thus. How’s this?

Then he, clever fellow, pointed out that some combination of the two might work, if we consider the knights as Soviets, as thus:

So that’s how things are going around here. I’m saving Art of Darkness for a graduate seminar or a book, and my Romanticism class is going swimmingly.

Girls are Strong

eople like this Paul Ford fellow, who wrote this otherwise excellent article about computer coding, are always holding up statistics like the following, presumably for our collective horror: “less than 30 percent of the people in computing are women.” We’re supposed to say: Can you imagine? That’s disgusting. etc. etc.

But man, 30%! That’s great!

People like this Paul Ford fellow, who wrote this otherwise excellent article about computer coding, are always holding up statistics like the following, presumably for our collective horror: “less than 30 percent of the people in computing are women.” We’re supposed to say: Can you imagine? That’s disgusting. etc. etc.

But man, 30%! That’s great! That’s way better than I imagined we were doing as a country! Not that programming computers is somehow noble, something to which all and sundry should aspire, but still, it’s (often) lucrative, which is something. But given that there are fewer women in the US workforce generally (47% according to the BLS) and that that number isn’t really right since, according to the same official statistics, 27% of those work only on a part time basis–presumably because they’re busy doing better things like birthing or raising the next generation of human beings so that there will be someone to use all this equipment–and since computer jobs tend not just to be full time, but all-consuming (hence the beds and food service at those “campuses”) so we’re really dealing with something like 35% of the workforce, and then peeling off the disproportionate employment of women in excellent, worthwhile, life-changing careers like education, then we’re down to something like perfect gender parity in computer-related fields. Which, again, doesn’t really matter any more than it matters that we achieve gender parity in sanitation collection–which we don’t have and no one complains about–but still, the tone bothers me. The mouth agape, “I thought we had evolved” look they all pose. Like we’re all supposed to be ashamed that some women tend to prefer spending time with other human beings, rather than staring into a blue-lit square for days on end, or that, worse still, the supposed imbalance is somehow calculated, somehow indicative of a pattern (to pull a metaphor from the both the worlds of coding–pattern recognition–and clothing, both fields to which women have complete access).

Note: all U.S. girls who have access to books or TV or films or other people know they can do anything they want with their lives. “Imbalance” based on self-selection is no cause for collective rue, still less for finger-wagging.

Chesterton and the Local

In a typically delightful essay called “What I Found in my Pocket,” G.K. Chesterton refers to "municipal patriotism” as "perhaps the greatest hope of England” (91). By this curious phrase, he means not love of country per se, nor civic machinery as such, but something more like love of the neighborhood. An odd claim, don’t you think?

In a typically delightful essay called “What I Found in my Pocket,” G.K. Chesterton refers to "municipal patriotism” as "perhaps the greatest hope of England” (91). By this curious phrase, he means not love of country per se, nor civic machinery as such, but something more like love of the neighborhood. An odd claim, don’t you think? He’s writing during the august reign of George V and all the political stability that era afforded. Chesterton wore a top hat and a cape. Only in a country whose empire spans exotica is dinner dress de rigueur for essayists. The banks of England were the very rock of Providence. Could none of these be reasonably considered the greatest hope of England? Chesterton was also a churchman. Dyed in the wool. An apologist, even. And that for a church still in its ascendancy, before parishioners went to watch television instead, found new gods in pop singers and bad science, and began converting the now-empty churches into pubs and fancy flats. Surely that strong church, light to the nations, would be Albion’s great hope. But no. Bored on a cab ride, the great writer puts his hands in his pocket, pulls out a lot of old train tickets from Battersea, his neighborhood, and nearly weeps for love of his particular pile of London.

Absurd as it may sound, I know just what he means. Having gone to work in England (2014-2015) I found myself turning out the proverbial pockets all the time, searching for scraps of home. It wasn’t America that I missed. Nor even Seattle, though that sometimes too. Principally, I longed for Queen Anne, an unexciting neighborhood contrasted with some, but mine. I mention any of this because the locavore movement is still gaining steam, and with it, detractors. “Let us all be citizens of the world,” the globalists say. And “to be local is to be provincial.” And most often, “hipsters suck.” I have never understood the hatred of hipsters. Aren’t they just cleverly dressed people who make conscience-driven consumer choices? The hats are silly, but who can hate someone in a silly hat? (see: Chesterton) Is it the independent businesses that arouse ire? The playing of children’s games in parks?

The more I see of the world, the less I believe in globalism. The truly international cities I loathe: New York, London. More local character, more distinctives, equal more charm: Dublin, Portland, Boston. Some people try to have it both ways.“Think globally, act locally” opines the bumper sticker. But even that axiom I question. By all means let us act locally (as if we could do otherwise.) But what’s the use of thinking globally? That I am aware of civic unrest in a part of the world I’ll never visit and from which I’ve never met a representative will net either of us exactly what? Is the idea that I’ll lend a hand if possible? So far, and from this vantage, all talk of globalism has led only too handwringing, the indentured servitude of coffee merchants, the destruction of Greece, and the occasional disastrous military intervention. No: the best way is to till the soil on which one was born, to love one’s neighbor, not firstly persons with whom one has no congress. Here I follow Wendell Berry of course, but also Mother Teresa who had it right when asked how she cared for tens of thousands of people, answering, "I didn’t. That would be impossible for one poor woman. I loved the one person standing in front of me.” Or something to that effect.

Elsewhere in the same collection of essays I picked up from a bookshop on the high street in Highgate, Chesterton recalls Walham Green, an indistinct bit of London that serves as an omnibus terminus. He’s on vacation in the picturesque Basque, with friends drinking and talking. Even in that lovely world and fine company, he longs even for the dull bit of planet that, only by knowing it, and walking around it so much, he’s made his. I think that’s wonderful.

“But compilers often do several passes, turning code into simpler code, then simpler code still, from Fitzgerald, to Hemingway, to Stephen King, to Stephenie Meyer, all the way down to Dan Brown, each phase getting less readable and more repetitive as you go.”

Romantics Class Recap: Faust 3

In class this week, we finished our reading of Faust, and buttressed our discussion thereof with a summary of sublime discourse from Longinus and Burke.

In class this week, we finished our reading of Faust, and buttressed our discussion thereof with a summary of sublime discourse from Longinus and Burke. The students selected passages in Faust that typified the sublime as Goethe renders it, noting especially:

- its ability to obliterate the sense of self

- to enlarge same

- to create fearful-pleasure (which led to an interesting discussion of roller coasters and horror movies. viz. is it because we trust amusement park safety mechanisms that we find such threats to our well-being pleasurable?)

- its sexual analogue, a correlation Mephistopheles makes (rather) explicit through coded stage directions

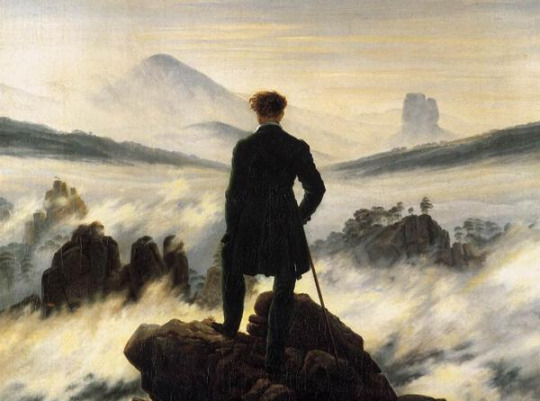

These led us to discuss the concurrent shift in painting, from the proud neoclassical heroism of Jaques-Louis David to the haunting, anti-humanist, perspectival work of JMW Turner and how the Romantic movement lives in the tension between those views, a pull best illustrated by that quintessential piece by Caspar David Friedrich: “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (1818) wherein the figure both rises above the chaos of the world–an image of the enlightenment artist–and is daunted, dwarfed by it, in an image of the Romantic one.

Finally, we discussed Faust as an aesthetic treatise. Before it is metaphysical, or merely entertaining, the play– as can be seen from the opening argument about what type of play it should be– interrogates both the place and power of art. We thought about how the materials of the world resist manipulation into form. From Michelangelo’s carrerra marble to the creation of lapis lazuli to the intrusion of “normal life” that wrecks the drive of so many aspiring artists, art-making is daunting business (on which subject the book Art and Fear is best). Somehow, this took us into recent work on evolutionary aesthetics and “the survival of the beautiful.”

All of these themes came to a head in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” which I recited (from my own translation). The poem blends all the elements of the sublime–the blindness, silence, mindlessness it engenders along with the arousal and fear and implications for self-understanding. And of course, it’s also a triumph of German (even of world) literature and a good deal of fun.

It’s my birthday! So I treated myself to @wearemacphun #Tonality app and made this first B/W conversion. Here’s me in my favorite hat, in Rome’s #Pigneto neighborhood.

Peter Stark "Astoria"

I saw this book on the shelf at the Edmonds Bookshop on my bi-monthly trip to the seaside town for tea.

I saw this book on the shelf at the Edmonds Bookshop on my bi-monthly trip to the seaside town for tea. I’ve never been to Astoria proper, but when I was a kid, we swam at nearby Canon Beach, and anyway, I’ve always been a sucker for Pacific Northwest history. Stark’s book is more popular (as in, written for non-specialist audiences) than I usually read, and it took a few chapters to get used to the lack of references, and the repetitions, but once I did, I flew through it. It’s part adventure story, part-historical recovery, and a large part what-if? Had a few events gone only slightly differently, the whole west coast might have been a country called “Astoria,” which Thomas Jefferson imagined as a separate, sisterly democracy to the U.S. Had other minor adjustments been made, or natural disasters allayed, all of Western Canada might have been added onto America. It was all so tenuous, and Stark’s gripping (and often moving) story gives us Astor and Jefferson as men of far-sighted vision while also giving us a memorable cast of players: some heroes, some villains, (though no one firmly in either camp) and as a backdrop to the suffering they endured and enacted, this whole, huge, terrifying west.

On Wheaton and Hawkins, by way of Percy Shelley

And now it’s the lead story over at The Chronicle of Higher Education. The new #Wheatongate continues apace and will likely continue so to do until the decision comes down from the Board of Trustees, at which point–whatever the decision–it will all flare up again until we find someone else’s business to be aghast over, or we forget. For the most part, I actually like this convtoversy for the level of conversation it has engendered.

And now it’s the lead story over at The Chronicle of Higher Education. The new #Wheatongate continues apace and will likely continue so to do until the decision comes down from the Board of Trustees, at which point–whatever the decision–it will all flare up again until we find someone else’s business to be aghast over, or we forget. For the most part, I actually like this convtoversy for the level of conversation it has engendered. People are having real conversations about the conflicting Muslim and Christian conceptions of God; others, in response to murmurs of racism from some quarters are bringing to light Wheaton’s sterling history on race, from its earliest days as a stop on the underground railroad through the abolitionist movement, through the hiring of its new college chaplain. The great Timothy Larsen has a piece on academic freedom with which I heartily concur on CNN. Still others are being thoughtful and quiet, which I think we could use more of.

The week, however, two faculty members broke silence to share what I believe to be erroneous readings of the situation, which I’d like to correct because it gives me a chance to bring up Romantic poets. Noah Toly has claimed and Alan Jacobs (of Baylor) has heartily seconded the following:

to the extent that the inadequacy of Dr. Hawkins response is the rationale for not reinstating her from her administrative leave, I am convinced the decision not to reinstate her was entirely misfit to the circumstances. To the extent that the initiation of termination proceedings emerged from that impasse, then I disagree with that step, as well.

Toly is right on a number of points in his response, and I’m thankful that he has supplied links to the supporting paperwork, including Hawkins’ theological statement to the college, but I think he underestimates this last bit. In short, Hawkins is not being terminated because of the hijab, or her edgy (misinformed?) theology, or even for stirring up media controversy against the college, but for refusing to participate in the reconciliation process. This is huge. Dr. Jones has himself said that her comments are fairly innocuous. They might be forgiven, clarified, all manner of things may be well. But her dropping off a 2.5 page note which is mostly quotations, saying in effect “this better be good enough because I’m not going to explain myself further” is an offense for which I believe she should be fired. Not only because it is unkind (though it is) and unprofessional (who, having served on college committees believes PR disasters are handled swiftly and completely via internal memo?), but because it shows her once again theologically unsound: she doesn’t know how reconciliation works.

In 1811, Percy Shelley made some similarly theologically-questionable statements in public while a student at University College, Oxford. When asked to clarify his views (to admit authorship, and likely to renounce the implications of the pamphlet) he refused to participate in the process. In a way, that’s a tragedy, because I think The Necessity of Atheism raises important questions, and because who knows what poetry we would have had from Shelley had he stayed in college? But even though the college had to eat their proverbial hat, erecting a memorial to the rebel some years later when he became the most famous alumnus of that storied institution, I think the administration was right in their decision. If you cross a line, there are ways of getting back, but one of them isn’t to reject the offering hand.

In this particular instance, I know whereof I speak. While a student at Wheaton College, I found myself, due to some undergraduate hi-jinks, called in by this same administration for disciplinary probation. Like Hawkins, I was questioned about my theological beliefs. Part of the reconciliation process the college offered was to require me to be in conversation with a spiritual mentor on a weekly basis, presumably to ferret out exactly what my problem was, and maybe also to keep an eye on me. It was a rich experience for me, having wide-open theological discussions in which I challenged every aspect of the faith statement and my interlocutor listened and responded patiently and intellectually. I said things that would make Larycia Hawkins blush. But–here’s the key difference–I was willing to play ball. “I’m not sure what I did was wrong,” I said, “and I’m not sure I believe the same things you believe, but I’ll go to the meetings and I’ll participate in the conversation.” That is what Hawkins is refusing.

The college has offered her a dialogue, a chance at full restitution, and the benefit of the doubt and she has responded with an ultimatum: fire me or don’t, but we’re done talking. Mind you, this isn’t after months and months of exhausting back and forth, but after one memo and one conversation. Her job, the college’s image, her students matter enough to her to warrant an afternoon’s work and no more. Her recent tone–”the college can’t intimidate me”–shows that Jones’ instincts have probably been right all along. She isn’t a team player and she doesn’t just want to get on with her work. She fires from the hip, saying un-thoughtful and divisive things, she seems to revel in tarnishing the college’s image (”you’re enrollment is going to suffer”) and will, when offered a map back into the college’s good graces, burn it, when offered the hand, bite it.

Which is why Toly is wrong: if much of it is questionable, nothing she has actually done in the past is fire-able, but her “unsatisfactory response” to the inquiry rather is, and good riddance. The most sensible clarification I’ve seen is, naturally, on the college’s website.

Finally, let me say that all these stories ended well. Shelley went on being a rebel and also managed to write some of the best poetry ever created in English; I was re-instated and allowed to graduate and later became President of the Wheaton Alumni Association of Washington. I love the school dearly. And I’m pretty sure all will work out well for Dr. Hawkins, who, if nothing else is showing a good bit of media saavy. She’ll likely be let go (what choice is she giving them?) and will likely appear on morning news shows as a victim, and she will almost certainly get an offer (probably a public one) from another university who will then look magnanimous compared with Wheaton. Likely it will pay a good deal more as well. The college will (and probably already has) suffer more than anyone else, but it will be fine, trying quietly to do its good work while the world screams and bleats around its ramparts.

Music/ 2015

Favorite records of 2015

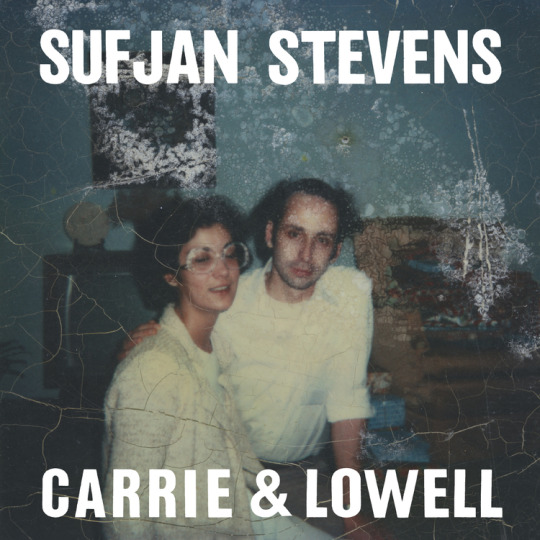

Sufjan Stevens

Carrie and Lowell

I’ve admired Sufjan Stevens’ music for a long time, but after BQE and Age of Adz I was ready to write him off as precocious, too obsessed with his own genius actually to make good music, instead making only good ideas. But this album brought it all back. Every bit of talent and musical inventiveness he has combines with honesty that’s more than precious, more than a posture here. Carrie and Lowell is not only my favorite record from this year; it’s one of my favorite records ever.

Waxahatchee

Ivy Trip

This is a new band for me. Waxahatchee have been making music for awhile in a homespun, stripped down style reminicent of early Bright Eyes records. They’re kind of anti-aesthetic, with little hushed or clean, and the album cover fairly shouts “we’re not going to be beautiful for you or anyone else!” but actually, they are. Truth is, I can harldy say why I like this record so much, but I’ve heard it every week this year, and when it’s not on, I think about when I can listen to it again.

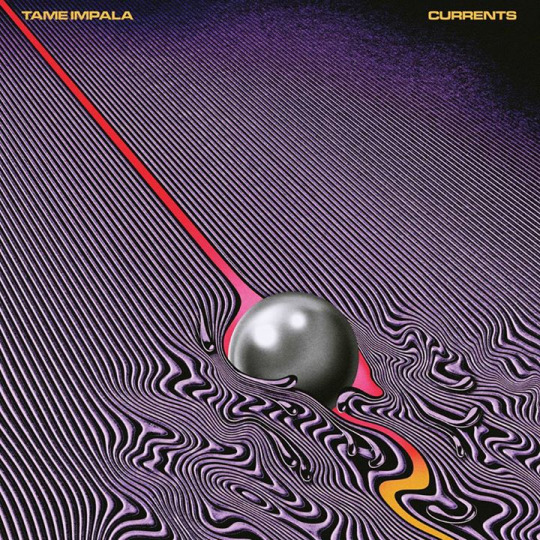

Tame Impala

Currents

Here’s another case in which the professional critics were right. It was a slow-grower for me, not as easily impressed by dance music as some. I kept playing this record mostly to see what some people saw in it. After awhile, it clicked. Song after song cleverly rewrote 80’s tracks, or else acted as though they had no inheritance whatsoever and where simply making music for the kind of world they thought this was or might be. It’s a hip record, but also kind of dorky; it’s futuristic and retro at the same time. As an educator, and a therefore a pitchman for difficult beauty, I appreciate having to work at art sometimes, and appreciate being taught.

Airborne Toxic Event

Dope Machines

Though the Airborne Toxic Event’s first record was one of my favorites of 2008, I didn’t expect to see much more from them. That record was so raucous, such a party, I thought surely they’d get the buzz out of thier collective system. Dope Machines doesn’t even sound like it’s from the same band, jangly guitars replaced with electronic loops, big Springsteenesque riffs flipped instead to faders and blips. But the attitude is still here, and the joy, and the sense of abandon that seems only possible among foreigners or drunks. This record makes me want to do everything better, but also to do it more somehow.

Grouper

Ruins

This record actually came out in 2014, and I listened to it some then, but I didn’t love it till this year. This whole rainy autumn back in the Pacific Northwest, it was one of the only soundtracks that made sense to me. Female-fronted like Waxahatchee, delicate like Sufjan Stevens, brave like Airborne Toxic Event, and true to its own (new) aesthetic like Tame Impala, Ruins wraps up everything I loved about music this year.

Teaching Cenci

I recently taught Shelley’s play The Cenci for this course at the University of Washington.

I recently taught Shelley’s play The Cenci for this course at the University of Washington. It struck me as “unstageable” for the same reasons it did so for the play’s early readers: the sexual episodes are too extreme for the (especially late-Romantic) stage, and the characters deliver exhausting monologues that would bore any live audience. Besides, the language is to full, so intellectual, that hearing it spoken by an actor, one loses half of the meaning. I know, Shakespeare managed to write just as rewardingly for the page and for the stage, but then, he was Shakespeare, wasn’t he?

But what a relevant play. The Cenci is a play about a corrupt Pope and bishopric turning a blind eye to sexual abuse in the parish. It’s about the powerlessness of victims and uneven appointments of justice based on gender and age: young people not able to stand up to their elders. So far, so applicable. It’s also a play about paintings, having been inspired by Guido Reni’s portrait. In that, it’s a play about ekphrastica, and historical reconstruction, which are at least as relevant (if less exciting). A recent debate about the painting’s provenancegave the class a kind of detective function, assembling the opposing arguments and adjudicating a real contemporary dispute.

Thank God, it seems like the Catholic church is coming out at last from a dark period in her history. For awhile there, the news had it that the church’s main business was settling abuse claims from 30 years ago. One hears less of that now, and more about the humble, graceful actions of Pope Francis.

The Cenci isn’t read much these days, I fear, neglected even among Shelleyan’s in favor of the weightier Prometheus Unbound, but short, provocative, and immensely rewarding, it should be.

“The Fellowship,” by Philip and Carol Zaleski

I’ve just finished reading The Fellowship, by Philip and Carol Zaleski, a group biography of the Inklings that evokes with extraordinary clarity images of clubmanship and bonhomie the group enjoyed between the wars.

For a real review of this fine work, see The Atlantic. These here are just some notes to self so I don’t forget that I just read a 500-page book.

I’ve just finished reading The Fellowship, by Philip and Carol Zaleski, a group biography of the Inklings, which evokes with extraordinary clarity images of clubmanship and bonhomie the group enjoyed between the wars. Not much of the material was new to me, having taught C.S. Lewis and the Inklings for the University of Washington, and having read biographies of Lewis by George Sayers and Alan Jacobs, as well as Lewis’ own Surprised by Joy and his Collected Letters, but the enigmatic figures satelliting the myth-maker (try as they might, no one manages to get Lewis out of the spotlight) find rather fuller expression here than they had had for me, and the group’s travails are depicted with the sympathy I think they deserve in this lively, ambitious book.

Clearly both researchers and fans, the Zaleskis sometimes blur the lines, allowing their affection for the characters (which who can fail to feel?) to overwhelm accuracy of assessment. For example, Tolkien dabbled in watercolors, and was a pretty fine draftsman, but his work doesn’t deserve the hushed tones the Zaleskis offer it, as though the world had ignored another Van Gogh in failing to grant him fame for it. Likewise, they discuss Lewis’ poetry as though it compared favorably to T.S. Eliot’s. They might even have been equal talents, the Zaleskis imply, had not public tastes shifted toward the modern under the don’s feet. But that’s not so. Lewis was wretched as a poet and as soon as he realized the fact, his whole world (and ours) grew richer.

Though they seem to have a hard time uttering criticism about these heroes, the Zaleskis rarely flatter concerning personal matters; a restraint I appreciate. Most biographers either ignore Warnie’s alcholism or wag thier fingers at him, as though dipsomania were fit subject for Sophoclean tragedy. The Zaleskis do neither, speaking plainly and seriously about his many hospitalizations without raising the proverbial eyebrow whenever we see him serving drinks.

They show a little less restraint on the subject of women, especially Dorothy Sayers, a tough, intelligent, successful, and deeply-admired figure who they have standing a the bottom of a tree house weeping at a hand-scrawled sign reading “No Girlz Aloud.” Several times they repeat the fact that no women attended Inklings meetings, but gentlemen’s clubs existed in the early twentieth century, as did ladies’ clubs. We need no more sigh at their social divisions than mock them for their ridiculously sluggish internet connections, especially when the circumstances so obviously suited all concerned. Who, seeing the Inklings’ corporate output (including Sayers’), could wish they had done things differently?

The Zaleskis give us an academically-robust Tolkien, which is a pleasant update to the picture Hobbit fans sometimes have of a professor phoning in his academic duties in service of his real passion for fantasy. And they give us also a Tolkien beautifully devoted to his family. He took each of his children on walks separately, for instance, acknowledging that they were different people with individual needs. About his wife Edith Tolkien believed:

‘nearly all marriages, even happy ones, are mistakes,’ as a better partner might easily have been found, but that nonetheless, one’s spouse is one’s real soulmate, chosen by God through seemingly haphazard events. Edith despite her lack of intellectual depth, her religious recalcitrance, and her fading beauty, was his real soul mate, and to her he pledged his body, his energies, his life (211)

The Fellowship also corrected my Lewis timeline somewhat. I knew he did well during his life, but didn’t have a sense of how popular Screwtape Letters made him. That many of the Christians who admire Mere Christianity did so first as radio broadcasts I knew, but not what blockbusters were the broadcasts themselves. I also liked Joy for the first time, who Debra Winger plays as Yoko Ono in the beautiful film Shadowlands, and who always seems like a hustler. She still reads partly that way, calculating circumstances so that she could ensnare the wealthy and famous writer, but in Zaleskis’ portrait, she’s so intelligent and successful in her own right that their partnership makes more sense than it had for me previously, and than it ever did for Lewis’ friends.

Finally, I like that the book showcases Oxford. The Inklings couldn’t have happened anywhere else and the city gets its due here; rather than stressing Ireland as some have done, or even the Kilns as others have, the Zaleskis give us a set of lives tangled around each other and an actual tangle of streets in that magic, holy place.

Christmas at the Movies

I’m a sucker for Christmas: while serious about the holy season, and against commercialism both generally and in its specifically American shopping bonanza iterations, I go in for the schmaltz and fanfare attached to the whole production with gusto

I’m a sucker for Christmas: while serious about the holy season, and against commercialism both generally and in its specifically American shopping bonanza iterations, I go in for the schmaltz and fanfare attached to the whole production with gusto. Eggnog intake I delay till Thanksgiving, else the proverbial cup would flow over for as long as I could maintain supply, and Christmas music I likewise prize and therefore restrict, but only just. And even though I don’t watch films either seriously or frequently, I make an exception for Christmas movies, which I love out of all reasonable proportion. In this area, as in so many others, the classics are best, especially Miracle on 34th Street (dir. George Seaton, 1947) and It’s a Wonderful Life (dir. Frank Capra, 1946). But the cartoons are lovely too:

- Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (dir. Larry Roemer, 1964)

- A Charlie Brown Christmas (dir Bill Melendez, 1965)

- Frosty the Snow Man (Rankin/Bass, 1969)

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas (Jones/Washam, 1966),who would have guessed the 1960′s would become the golden age of children’s Christmas animations?

- Mickey’s Christmas Carol (dir. Burns Mattinson, 1983) which Disney has made extremely difficult to find over the years, releasing similarly-titled replicates, and other “Mickey’s Christmas” collections that don’t feature this, their best work.

And of course I enjoy more recent contributions.

- Christmas Vacation (dir. Jeremiah Chechik, 1989)

- A Christmas Story (dir. Bob Clark, 1983)

- Elf (dir. Jon Favreau, 2003)

- Love, Actually (dir. Richard Curtis, 2003) about which I wrote in defense against some haters here.

Some of them I like very much indeed, but I don’t quite number with the earlier perfections. When one has seen all these films dozens of times, one seeks to broaden the range of fare, and is often disappointed. On the advice of some lists, I watched The Bishop’s Wife (dir. Henry Koster, 1947) last year, and found it–though I love Cary Grant–both heartless and profane. But sometimes, or, twice anyway, I got lucky. Because I sense they’re not watched as often as the films listed above, because the genre is full of pitfalls, and because people are generally loathe to watch b/w films and might therefore need a push, let me recommend, for those who’ve exhausted the usual set, two more.

- The Shop Around the Corner (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1940)

- Holiday Affair (dir. Don Hartman, 1949)

I found these films winning and wise, pretty, and a great deal of fun. They might even be my new favorites, which I now have to be careful not to overplay.

Merry Christmas!

Should I really buy another Mac?

I’m having a great time teaching here at Northwest. Though my office is windowless, I have some lovely lamps and a comfortable writing chair.

Unfortunately, I also have a PC.

I’m having a great time teaching here at Northwest. Though my office is windowless, I have some lovely lamps and a comfortable writing chair.

Unfortunately, I also have a PC. The Optiplex 790, to be exact, loaded with Windows 10 (I think) and it’s every bit as terrible as you–lovers of beauty, users of Macs–imagine it would be. Who knew one could still burn up so much time “setting-up” a desktop computer? I’ve got everything synced up on Dropbox-the-magnificent, but 90% of those files are made with Pages, which Word, somehow still can’t read. So I tried the magical new iCloud for PC program, allowing PC folks to see what life is like for the better half, but even that is riddled with difficulty. For one, I can’t figure out a reasonable file structure. Do I transfer my whole dropbox hierarchy over to iCloud? If so, I have to separate my logical project-based structure into the native app-structure. My scans of mid-Victorian Scottish paintings meant to accompany a forthcoming article on Alexander Smith’s travel writing can no longer live in the sensible “Summer in Skye” folder, but have instead to go hang out in “Preview.” Yuck. Plus, clicking the Pages icon on the PC opens only an old version of Internet Explorer, despite that the machine is loaded with MS Edge, and Google Chrome.

I keep trying to better this writing experience by making the interface more mac-like: stripping away the silly backgrounds, removing the tiles, and spending all my time in the iCloud web-interface, but something is still not right. One wants to be adaptable, naturally, but this bilingualism is simply eating the hours. Today, I ordered an iMac keyboard, since even the low-profile Dell I special-requested feels like a typewriter compared with the swift, low space I’m used to. I’d suck it up and buy a desktop iMac, but it won’t talk to the network here in any way: I asked the IT team already. Impossible to print to the department machine ten steps away they tell me. Do I use a Mac anyway, “printing” to Dropbox, sign in to a nearby computer set up as a print station? Do I buy a printer for my office and forget the network altogether? Do I just set up iCloud more intuitively and, when I get my new keyboard, make the best of it? How is this still so hard?

Teaching Cenci

I recently taught Shelley’s play The Cenci for this course at the University of Washington. It struck me as “unstageable” for the same reasons it did so for the play’s early readers: the sexual episodes are too extreme for the (especially late-Romantic) stage, and the characters deliver exhausting monologues that would bore any live audience. Besides, the language is to full, so intellectual, that hearing it spoken by an actor, one loses half of the meaning. I know, Shakespeare managed to write just as rewardingly for the page and for the stage, but then, he was Shakespeare, wasn’t he?

I recently taught Shelley’s play The Cenci for this course at the University of Washington. It struck me as “unstageable” for the same reasons it did so for the play’s early readers: the sexual episodes are too extreme for the (especially late-Romantic) stage, and the characters deliver exhausting monologues that would bore any live audience. Besides, the language is to full, so intellectual, that hearing it spoken by an actor, one loses half of the meaning. I know, Shakespeare managed to write just as rewardingly for the page and for the stage, but then, he was Shakespeare, wasn’t he?

But what a relevant play. The Cenci is a play about a corrupt Pope and bishopric turning a blind eye to sexual abuse in the parish. It’s about the powerlessness of victims and uneven appointments of justice based on gender and age: young people not able to stand up to their elders. So far, so applicable. It’s also a play about paintings, having been inspired by Guido Reni’s portrait. In that, it’s a play about ekphrastica, and historical reconstruction, which are at least as relevant (if less exciting). A recent debate about the painting’s provenancegave the class a kind of detective function, assembling the opposing arguments and adjudicating a real contemporary dispute.

Thank God, it seems like the Catholic church is coming out at last from a dark period in her history. For awhile there, the news had it that the church’s main business was settling abuse claims from 30 years ago. One hears less of that now, and more about the humble, graceful actions of Pope Francis.

The Cenci isn’t read much these days, I fear, neglected even among Shelleyan’s in favor of the weightier Prometheus Unbound, but short, provocative, and immensely rewarding, it should be.

On Fascism, of course

I tend to disagree with everything Adam Kirsch says; even if he’s telling a story about his own life, I have a hunch that he’s lying. It all just sounds false to me, especially his poetry. This article, sent on my @prufrocknews is no exception; especially this bit:

It was at a party in early 2002, a few months after the Sept. 11 attacks, that I first heard someone declare, as if it was self-evident, that the George W. Bush Administration was fascist. The accusation refuted itself, of course—people living under a fascist regime don’t go around loudly attacking the regime at parties—but it was symptomatic of the times. Post-Sept. 11 paranoia took many forms, and one of them was paranoia about the American government (and not just in “truther” circles).

I hate the “of course” because it’s a verbal arrogance to which I’m prone as well. It presumes that what one is saying is evident to any thinking person, which Kirsch’s claim here is not. “People living under a fascist regime don’t go around loudly attacking the regime at parties” he pronounces, settling the argument in a way somehow both definitive and obvious. I don’t know what kind of parties Kirsch attends, but, actually yes, they do. There is not now, nor has there ever been, a fascist/totalitarian regime so powerful that no person at no party would dare criticize it. Not Stalin, not Mao, not Ayatolah Komeni, not Bush. And there has especially never been a regime structured such that the presence of criticism ceased to make it fascist. Insufficiently in control, perhaps. A government can control many things, can limit press and squash dissent but only when that dissent is sufficiently public.

Fascist governments are those which seek to enforce conservative values and behavior norms and engage in–to greater or lesser degrees, depending on the totality of their power–governmental suppression of individual freedom. You can read the Bush administration as having done such things or not, but it is not obvious that they did not. Pretty fair cases have been made that, on dozens of occasions, they sought to enforce certain behavior norms, and to limit personal freedom in the name of conservative values. Critics of the administration were fired from their jobs, scientists who suggested alternative theories about climate change were denied grants and subject to derision, an undercover agent was apparently outed (and could have been killed) for disagreeing with the march to war, and a group of pop singers who criticized the president was publicly tarred and feathered, threatened with death, and radio stations that played their music with boycotts, to cite some of the memorable, if not the most egregious, examples.

Unfavorable estimates of Bush’s tenure abound; the people who hold them may be, but are not necessarily,as Kirsch claims they are, “paranoid,” or “symptomatic,” or sick. They just disagree with you. Mmm…kay?

Music/ 2014

My favorite records.

Temples

Sun Structures

Sun Structures is one of those rare records I liked from the first note. After that, I liked each song better than the one before it and a hundred or so listens has done nothing to blunt that first thrill. It's big hooky Brit-rock, but dirty, and full of fun musical references to bands from way before any of these lads were born.

War on Drugs

Lost in a Dream

Here's a case where the people's voice was dead on. The album topped every respectable year-end list, and for good reason. It's a bit of a grower. At first, one doesn't see what the big deal is with what sounds like a Springsteen cover band, but the deeper one goes into the dream, the more the album's patience and musicality reveal themselves.

Damien Jurado

Brothers and Sisters of Eternal Son

Pretty much every year that Damien Jurado releases an album, it makes my Best-Of list. No two of them are really alike, some heavy rock, some country-folk, some space-age pop. I love every single one out of all proportion. If I had to pick one artist to listen to, to the exclusion of all others (horrid world, that) I wouldn't hesitate to select Jurado. This album is psychedelia--not my usual cup of tea--and it took a month or so to understand what was going on here. Now, I think about this record even when I'm not listening to it, wondering how its doing and how long we'll have together.

Spoon

They Want my Soul

I've loved Spoon since 2002's Kill the Moonlight, but between that record and this, though I've adored some of the singles, none of the albums caught me quite right. This one brings it all back home: the swagger, but also the joy. This album is a band in top form. It's like watching Achilles in battle; not only like they won't miss a step, but like they can't somehow.

Future Islands

Singles

This album defines my time in London more than any other. I rode the tube for at least two hours every day, so I listened to tons of music, including most of the albums on this list, thanks to the new deep-bench streaming services. I started listening to Singles before I knew anything at all about the band, finding it compelling--oddly confident, throw-back lounge music but somehow unmistakably of-the-moment. Then I saw the band's beautiful performance on Dave Letterman and was hooked.

Hardly Hedgerows

Digging through early biographies of the Wordsworth, M.E. Bellanca uncovers one by the poet’s nephew Christopher called Memoirs of William Wordsworth, published in 1851. It features, as she notes, heavy quotation (about 45 pgs) from Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere and Scotland journals. So, it should be considered an early publication of Dorothy’s, refuting years of scholarship that had claimed that Wordsworth’s talented sister remained unpublished during her life.

Except scholars made no such claim.

“After Life-Writing: Dorothy Wordsworth’s Journal in the Memoirs of William Wordsworth.” by Mary Ellen Bellanca. European Romantic Review 25:2, 201-218.

Digging through early biographies of the Wordsworth, M.E. Bellanca uncovers one by the poet’s nephew Christopher called Memoirs of William Wordsworth, published in 1851. It features, as she notes, heavy quotation (about 45 pgs) from Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere and Scotland journals. So, it should be considered an early publication of Dorothy’s, refuting years of scholarship that had claimed that Wordsworth’s talented sister remained unpublished during her life.

Except scholars made no such claim. In the examples Bellanca herself gives, both William Knight and Ernest de Selincourt mention the excerpted passages. For Bellanca, the credit they give diminishes Dorothy’s contribution, by calling them “a few fragments,” and “short extracts.” From there, Bellanca builds a case for Dorothy’s talent, and her womanly victimization at the hands of a masculine society that didn’t appreciate her intellect.

Bollocks. Dorothy was reverenced by her brother, enshrined in his best poems, noted constantly as an inspiration (even a crutch), and respected for her observation and quick wit by his friends. History has treated her very well indeed. Though she was meddlesome, and eventually lost her mind, she is probably the most respected female figure of the Romantic era, apart from Mary Shelley. I can conjure no image of sibling affection stronger than William and Dorothy Wordsworth. Editions of her work abound. College seminars and graduate dissertations interpreting it flourish.

Bellanca’s reading is ideologically driven, but it isn’t a screed. It’s well-written, especially examples from the Memoirs, and command of the Wordsworth’s reception history. But as ideologies do, the feminism blinds her to more logical interpretive possibilities. “Invested in a gender ideology that exalts Dorothy’s devotion to her brother, the Memoirs…casts her in relation to William,” she chirps (204). See the problem? There’s no reason to think that Christopher Wordsworth exalts familial devotion as a consequence of his investment in a gender ideology. We’re talking about his aunt and uncle. The degree to which they are devoted to one another, or are represented as devoted to one another reflects on his immediate heritage and values. “My aunt and uncle were very close,” reads more convincingly as “I come from a good, moral family” than “women are worthless apart from their servile attachment to powerful males.”

Other overstatements diminish the paper’s real import. Recall that Christopher didn’t likely possess the literary trove a modern biographer might, but certainly had access to family papers, such as Dorothy’s journals. Bellanca claims “the extracts reveal [Dorothy’s] centrality to the poet’s work,” which is saying too much by half. (24). “Centrality” is wrong. No matter how important she was for William—and she was quite important— she was in no way central. It isn’t as though he writes exclusively, or even mainly about his sister, though she plays ancillary roles in a few poems. One might claim that she was central to his life, although that would exaggerate too, but that she was central to his work is insupportable. Also, such overstatements cast her in relation to William: exactly the sin of which Bellanca accuses Christopher Wordsworth. Dorothy’s writing is good and worthy of study; she was also a good and helpful sister, even a sometime muse for her more-talented (or simply more productive?) brother. More than this need not be assumed.

Two more points. The paper concludes with the conjecture-cum-accusation that Dorothy may not have been consulted regarding the publication of journal extracts for her brother’s Memoirs. “One must wonder," the article wonders, " whether she consented to, or was even aware of, the printing of…her writing for strangers to read” (214). Bellanca calls this “troubling,” or, since like most of her claims, this one vacillates, “potentially troubling” (214). How so? The first ¾ of the essay contends that Dorothy is an important author in her own right who ought to be respected as such. The last quarter suggests that she may have been scandalized by publication. Which is it? Bellanca doesn’t seem to know, referring to “her desire or non-desire to be read” (214). In what way would it be “troubling,” for her relatives to publish works she intended for publication? Especially a publication that honors her brother’s memory, whom she had spent so much of her own life honoring and encouraging? The conjecture is unhelpful, particularly the air of grievous offense cast over the proceedings, as though the poor woman were taken advantage of.

Worse still, Dorothy may just as well have been consulted and consented to the publication. At the time, Dorothy was 80 years old, and, as Bellanca notes, “often incoherent” (214). Even at that, her family may have asked her, and may have had a positive, coherent response. We simply don’t know. Bellanca doesn’t know. That doesn’t stop her from implying wrongdoing, alas. “It would be highly ironic if this very private writer…had been conscripted into the public visibility of the print market without her knowledge, or permission” (214-5). That’s a big “if.” And if she were senile, it wouldn’t even be that, but due course: we have no moral qualms about publishing good writing, whether intended for publication or not, by persons deceased or otherwise incapacitated, who occupy important roles or historical perspective.

In a last jab, Bellanca wonders in the footnotes (but of course she never wonders; she accuses), “how did literary history forget…that Dorothy Wordsworth was a writer to be taken seriously,” between the publication of the Memoirs in 1851 and the 1970’s, when she was “recovered”? Predictably, and offensively, Bellanca suspects “such factors as…the rise of professional literary studies with a predominately male professorate” (216). That’s absolutely unfounded, and juvenile. It’s small-minded to imagine that no one acts apart from the interests of their group, especially professional scholars, concerned with aesthetics, influence, history, data, among much else. False historically too, since Austen, Sappho, Aphra Behn, the Bronte’s, George Eliot, Christina Rossetti, Mary Shelley and other women to numerous to name enjoyed ample (if not equal) attention during the same period of Dorothy’s "neglect."

But she wasn’t even neglected during the interim Bellanca outlines. First, the 1851 Memoirs didn’t vault Dorothy to prominence; they introduced her as an important figure to people who already knew and liked William. Dorothy’s work didn’t achieve prominence will 1884-1902, as Bellanca notes elsewhere. So we’re not talking about a 100+ year gap in attention for whose obvious error we need a scapegoat. If she’s prominent in 1902 and we imagine a gradual, rather than a sudden descent, let’s say interest tapers till the mid-1930’s (counting the number of dissertations and books). That leaves only 40 years till her “revival” in the 1970’s, or not quite half a human life. Assigning that gap a negative valuation, seeking someone to blame for it, and finding that blame in sexism all seem to me intellectually irresponsible. If an explanation were required (again, it is not) more likely culprits emerge.

Genre, for one. What is Dorothy’s writing? They’re not poems (as I see it, and importantly, as most literary scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries saw it, the most important things a person can study), not fiction, not even memoir, quite, but journals whose author may or may not have assented to publication. That’s pretty rarified air. Does one teach them in a History of Poetry class? If there is any sense in which Dorothy’s reputation suffered for a short span in the middle of the twentieth century, it is as likely due to circular needs as anything so nefarious as Bellanca’s Black Shirt New Critics, or Gang of Six, or the Great Satan himself: men.