Romantics Class Recap: Faust 3

In class this week, we finished our reading of Faust, and buttressed our discussion thereof with a summary of sublime discourse from Longinus and Burke. The students selected passages in Faust that typified the sublime as Goethe renders it, noting especially:

- its ability to obliterate the sense of self

- to enlarge same

- to create fearful-pleasure (which led to an interesting discussion of roller coasters and horror movies. viz. is it because we trust amusement park safety mechanisms that we find such threats to our well-being pleasurable?)

- its sexual analogue, a correlation Mephistopheles makes (rather) explicit through coded stage directions

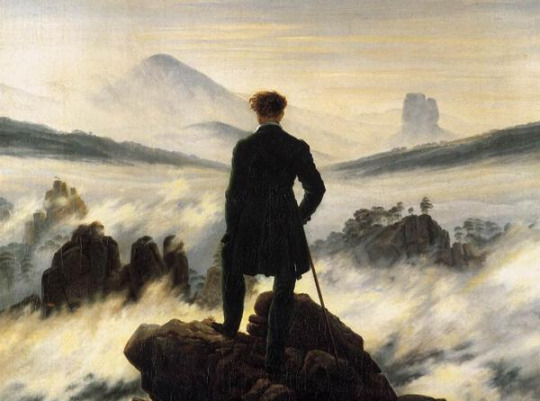

These led us to discuss the concurrent shift in painting, from the proud neoclassical heroism of Jaques-Louis David to the haunting, anti-humanist, perspectival work of JMW Turner and how the Romantic movement lives in the tension between those views, a pull best illustrated by that quintessential piece by Caspar David Friedrich: “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (1818) wherein the figure both rises above the chaos of the world–an image of the enlightenment artist–and is daunted, dwarfed by it, in an image of the Romantic one.

Finally, we discussed Faust as an aesthetic treatise. Before it is metaphysical, or merely entertaining, the play– as can be seen from the opening argument about what type of play it should be– interrogates both the place and power of art. We thought about how the materials of the world resist manipulation into form. From Michelangelo’s carrerra marble to the creation of lapis lazuli to the intrusion of “normal life” that wrecks the drive of so many aspiring artists, art-making is daunting business (on which subject the book Art and Fear is best). Somehow, this took us into recent work on evolutionary aesthetics and “the survival of the beautiful.”

All of these themes came to a head in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” which I recited (from my own translation). The poem blends all the elements of the sublime–the blindness, silence, mindlessness it engenders along with the arousal and fear and implications for self-understanding. And of course, it’s also a triumph of German (even of world) literature and a good deal of fun.