Bronte the anti-Austen

Here’s an essay idea that I'd like to think I'll return to someday, but given the backlog of scholarly journal articles I’ve already committed to, I can't see when that will be, so I'll just put this germ of a thought here for now.

Charlotte Bronte's Shirley shows the novelist to be Jane Austen's superior (a la Harold Bloom's anxiety of influence) by using the same technique of writerly asides, but with reasonable boundaries. With them, she pulls readers into her confidence, sets pace, establishes the parameters of the known, and shows herself (not merely the characters) to be charming besides. She's making a whole world come alive, but exhibits no strain whatsoever, reels it out as if on a string, laughing all the way.. Following a description of Caroline Helstone's appearance, for example, Bronte writes: “As to her character or intellect, if she had any, they must speak for themselves in due time" (75).

Anti-Austen, that. Not only can Bronte render an archetypal Austenian “sketch,” she can toss them off at will, can toss them aside thereafter as if inconsequential. What she will not do, and it makes Austen seem silly by contrast (note: I think Austen is a wizard, a genius) is deign to tell we readers about the woman's inner world. Those judgments the reader must make for himself. The technique makes the narrator seem less omniscient and therefore less pedantic, but also builds suspense as we wonder: yes, but what will she be like?

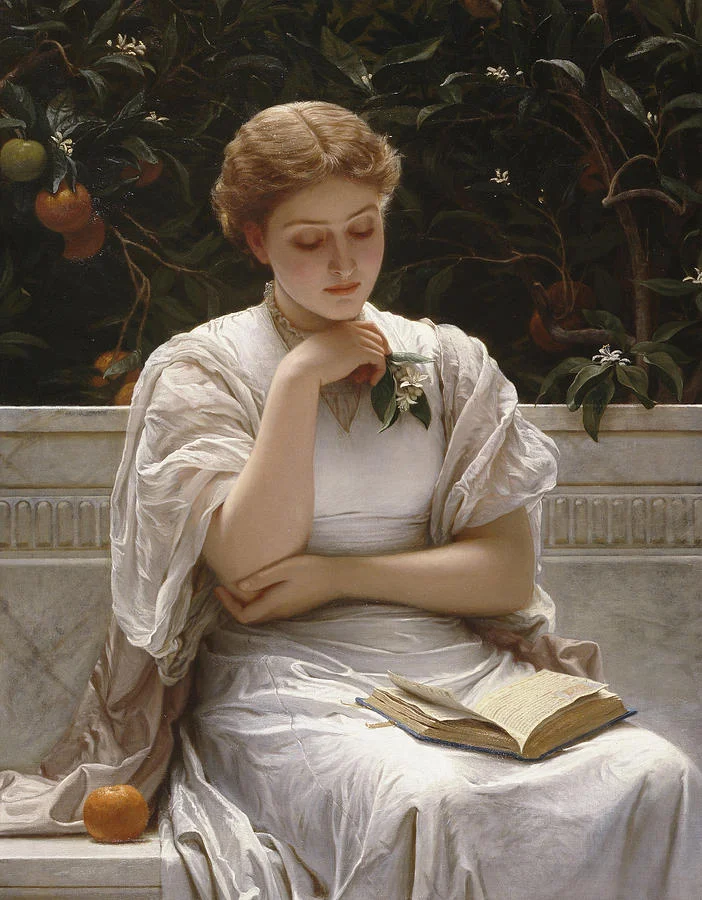

Also--and this is only sort of related to the above--the novel says much about women and education. Perhaps it will take a turn toward lament soon, but in the early chapters, the picture of Caroline's education is pure honey. There she is reading and memorizing French poetry in the following setting: "sitting in sunshine, near the window, she seemed to receive with its warmth a kind of influence, which made her both happy and good" (75). Can a better fate befall one? Sunshine through a window, warmth on the skin, book in hand? I very much doubt it.