My Brief Affair with the Criticism of Michael Robbins

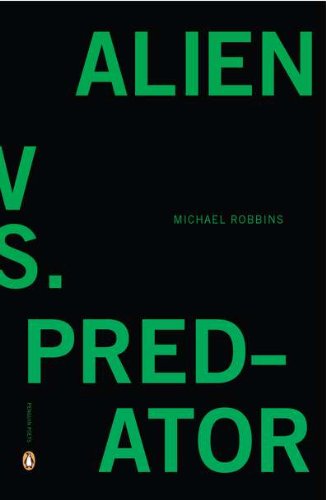

Well, that was quick. On Wednesday, I received my copy of this month's Poetry Magazine, and read the criticism first, as is my custom. There, I found a blistering--not for its spirit, but for its force--critique of a new anthology called Postmodern American Poetry: A Norton Anthology, edited by Paul Hoover. It was authored by one Michael Robbins, whose poem book, "Aliens vs. Predator," I ordered immediately. It hasn't yet arrived, so I don't know if it's any good, but the essay is so smart, so broadly associative, so powerful in its judgement, that I tweeted this, right away.

You can read the essay here. I was convinced that we had another Randall Jarrell in the making, combining sound judgement with elegant prose, and the kind of energy and good humor you might expect from someone who would name his book after Arnold Schwarzenegger franchises. I shoved the essay into anyone's hands who had ever expressed a passing interest in verse-making. "Excited" doesn't begin to cover it; for whatever reason, well-written criticism lights me right up.

Our affair was beautiful and passionate, and has now burned itself out. A few days following the Poetry Magazine piece, Robbins published another article in the Chicago Tribune (read here) which is defensive and under-theorized, and frankly, juvenile. In it, Robbins defends song-lyrics as poetry, which people who know nothing about either song-writing or poetry, do all the time. That's one of the problems: that there isn't anything original about the claim; people (usually rappers and their vociferous following) are always claiming that there is no difference between what Kanye West does and what Anne Carson does, as though to deny the rich, famous, aggressive and universally-admired TOTAL control over every provenance their enterprise touches amounted to a kind of snobbery. The other problem with the article is that Robbins' argument comes down basically to a) song lyrics=poetry because Bob Dylan is super awesome, and b) because why not? Quote: 'What would be the point of denying these lyricists the honorific of "poet"?'

For one, "poet" isn't an honorific; it's a job title. It's a job title for people who make real the inherent music in words, and not one for people who make music, and then add words to it. If that seems like a small difference to you, consider the difference between a bicycle and a motorcycle. Two wheels, seats, vehicles of transport. But, if the motorcycle is "cooler" somehow, it relies on an external source of power to get where it's going. The same is true of song lyrics: without the music, they're just a bunch of metal sitting in a garage. Stay with the metaphor for a moment. A bicycle is powered by whoever happens to be riding it. Some will be better than others, some can do tricks on it, but bikes work (or don't) in large part based on the training, practice, talent of the rider. So too the poems on the readers'.

There are far more arguments against this tired position than I feel like trotting out here; a well-written version of them can be read in this essay by William Logan, which came out in this month's New Criterion. Logan isn't really arguing the point, he just takes the distinction as a given that educated (or grown-up) people maintain. Here's some of it though:

Song lyrics can be entirely artless or devilishly contrived, composed by some magician of the word or just some putz; but whatever they are they need music to make them art, and without music they’re just love without money. “Sha-na-na-na, sha-na-na-na-na” and “Do-wah-diddy-diddy-dum-diddy-do” and “Ob-la-di, ob-la-da” make perfectly wonderful lyrics, but on the page they look like gibberish. Cut out the tune, and lyrics are just words that look annoyed.

Logan is right en pointe here. One of my favorite differences is that poems are in their truest, most authentic possible performance in every individual reading. If Yeats came back to read "Adam's Curse," there would be no reason to take his choices of inflection as more correct than mine; if Tennyson read "Ulysses" like he were on helium, he wouldn't--he couldn't--damage the poem, because a poem re-incarnates in between every set of lips that shape it. Obviously, the same is not true of lyrics. Dylan has to be there for a Dylan song to work. When he's dead, there can be no more authentic Dylan performances, while Keats performances will continue, in all possible originary power, as long as we have breath and books (or memory).

...which is all to say that I should have listened when Robbins tweeted me: