Toward a Resurection Aesthetic

He practiced jumping, getting big, breaking some bricks with his head. And then he fell down one of those mine shafts they have everywhere and died…

“But you have another life,” I said. “Look at those hearts.”

Between the Joints and the Marrow by Garrett Soucy

There isn’t anything affected in either Garrett Soucy’s singing voice or his literary style. Both are spare as a cabin in the Maine woods, a cast iron stove in the corner for heat, but also for hardness. Sometimes when walking, one comes upon the remnants of such a place, a chimney that has out-lasted its house. That’s these poems: compelling, comfortable, and classic as brick.

“There isn’t anything affected in either Garrett Soucy’s singing voice or his literary style. Both are spare as a cabin in the Maine woods, a cast iron stove in the corner for heat, but also for hardness. Sometimes when walking, one comes upon the remnants of such a place, a chimney that has out-lasted its house. That’s these poems: compelling, comfortable, and classic as brick.”

Which Seeds Will Grow by Andrew Calis

"Scattered about, some seeds surely fall on the road, some are choked by weeds, and others fall on good soil and sprout. The work of Calis’ weighty new collection is to see all of them—the bloomed and fruiting ones along with the choked and trampled—as a testament to the long, slow, and holy struggle toward cultural healing, nourishment, the light."

“Scattered about, some seeds surely fall on the road, some are choked by weeds, and others fall on good soil and sprout. The work of Calis’ weighty new collection is to see all of them—the bloomed and fruiting ones along with the choked and trampled—as a testament to the long, slow, and holy struggle toward cultural healing, nourishment, the light.”

Which Seeds Will Grow

Andrew Calis

Paraclete, 2024

Exit, Pursued by a Presbyterian

Some critics, theater-goers, and directors enjoy this scene simply because it seems so random: here we are in a very serious play about jealousy and power imbalance, rage and injustice, gift-economy and indebtedness and now this crazy bit of text suggesting, what exactly?

I'm indebted to Frederick Buechner for many things: for his helping to sort out my faith when I was ready to walk away from it in my twenties, for his demonstration of the rippling effects of suicide on a family which has kept me from committing a sin by which I've been sorely beset, for his calling up the inherent musical possibility of prose sentences—their Janus-faced, Chestertonian grace—that made me want to be an essayist as well as a poet, and especially for his sorting out what is now my theory of evangelism: that it doesn't start with sharing The Story, as one might tell it out on a string of beads beginning with green for Eden, then black for sin, etc.; rather, it begins with sharing The Author as He has written, and has been writing, my story, or as Buechner memorably-as-ever, phrased it,

Listen to your life. See it for the fathomless mystery it is. In the boredom and pain of it, no less than in the excitement and gladness.[1]

I've been trying to pick out that lead of Love ever since reading his biographies decades ago, and by Heaven's grace, sometimes even successfully. But in addition to all that, recently, I've been grateful to the good Reverend for helping me make sense of Shakespeare's strangest stage direction.

It's famous; you've probably heard it. In the middle of The Winter's Tale, when the lost child Perdita is set among the rocks, exposed to whatever death or happenstantial rescue might find her, poor Antigonus—the servant in charge of setting the supposed-bastard out as a foundling that the kingdom might not be defiled by the act that King Leontes wrongly imagines begat her —is chased off-stage with a curt ‘Exit, pursued by a bear’ (iii.3.65). It's a fun bit of artistic assignment as generations of directors are given a practical problem to solve. In Jamesian England, maybe they used a live bear from the bear-baiting shows that often preceded a night at the theater. Do we make a bear costume and have an actor stage the chase? Should it be funny? Animated? What if we used a stuffed teddy and Antigonus just acts terrified? Some critics, theater-goers, and directors enjoy this scene simply because it seems so random: here we are in a very serious play about jealousy and power imbalance, rage and injustice, gift-economy and indebtedness and now this crazy bit of text suggesting, what exactly? I think I know now and I know I wouldn't have noticed were it not for Buechner's relation of his experience of teaching King Lear at Phillips Exeter in Telling the Truth (1977).

Buechner refers to the ‘tragic vision’ of King Lear, ‘in which the good and the bad alike go down to dusty and, it would seem, equally meaningless death with no God to intervene on their behalf’,[2] but he also calls the same play ‘a homily’ on 1 Corinthians 1:27-28 because,

[It] points to the apparent emptiness of the world where God belongs and to how the emptiness starts to echo like an empty shell after a while until you can hear in it the still, small voice of the sea, hear strength in weakness, victory in defeat, presence in absence.[3]

But if Lear is a gloss on the silence/absence of God in which He is still active, as above, Winter's Tale is all presence. True, villainy thrives, evil denounces good, jealousy destroys ancient friendships, and families are torn asunder. And yes, children—the least of these—suffer, but for all that, the universe in the play is fundamentally just. In fact, justice seems to be the central feature of the cosmos therein, one more profoundly woven into the fabric of existence than, for example, the laws of physics or biology.

While the unlucky Antigonus argues that he’s just the means for the injustice he’s about to commit—I was just following orders—some part of him senses a divine retributive justice at work, of the sort Buechner identifies in Lear, saying ‘I will be squared by this’ (iii.3.45). Here too, as in Lear, the world and weather seem to agree. While the day is fine over at the oracle of Delphi, which detail is meant to convince a Christian audience that we can trust what it says, the sky over Perdita and Antigonus ‘looks grimly/ and threaten[s] present blusters’ (iii.3.4-5). Everything is lining up to perform justice, despite humans’ best efforts to deny it. And, of course, this culminates in ‘how the bear tore out his shoulder-bone…how the poor souls roared and the sea mocked them; and how the poor gentleman roared, and the bear mocked him’ (iii.3.99-107). God is not mocked. Why a bear and not, for example, a wolf? Because we later find out that Hermione is descended from Russian nobility: the spirit of her homeland, like the sea and sky itself, has conspired to ‘show the heavens more just’ (Lear, iii.4.41).

It is a consistent vision, one not limited to Leontes' repentance and Hermione's eventual restitution. It's fundamentally an incarnation, one where God very much intervenes on behalf of the innocent. In another example from Winter’s Tale, grown Perdita is talking with a disguised Florizel about how she, apparently a mere shepherdess, could possibly bridge the huge distance in class to marry the prince. Wasn't it ridiculous for them to be talking this way? Florizel brushes the complication aside with a wave of his hand:

[…] The gods themselves,

humbling their deities to love, have taken

The shapes of beasts upon them.

He lists Jupiter, Neptune, and Apollo as examples—recall that this is intentionally a pre-Christian play—of this incarnation. Yes, he says, the distance between us is real, but a god can come down from heaven to be with those he loves.

City Nave by Betsy K. Brown

The poems in City Nave twist and slither off the page, never still, ablaze one breath and ashen the next, here admonishing, there searching, always, like a Phoenix, fiery, always re-birthing.

Rabbit Room Poetry with Ben Palpant

Any work that's taking chaos and ordering it is co-laboring with the Holy Spirit…

Let Go the Goat Podcast w/ Mike Rippy

The earliest stirrings of a literary response were hearing my mother read King James Bible.

Faith and Imagination Podcast w/ Matthew Wickman

It’s the realest thing that happens in my week.

Why I Go to Church

Church is a lot of things for me: the center of my social and artistic life, the place I practice my actual talents, for music, for leadership—but I love it in part because I’m a weakling who can hardly stand to stand up most mornings and the church was made for, and needs, people like me.

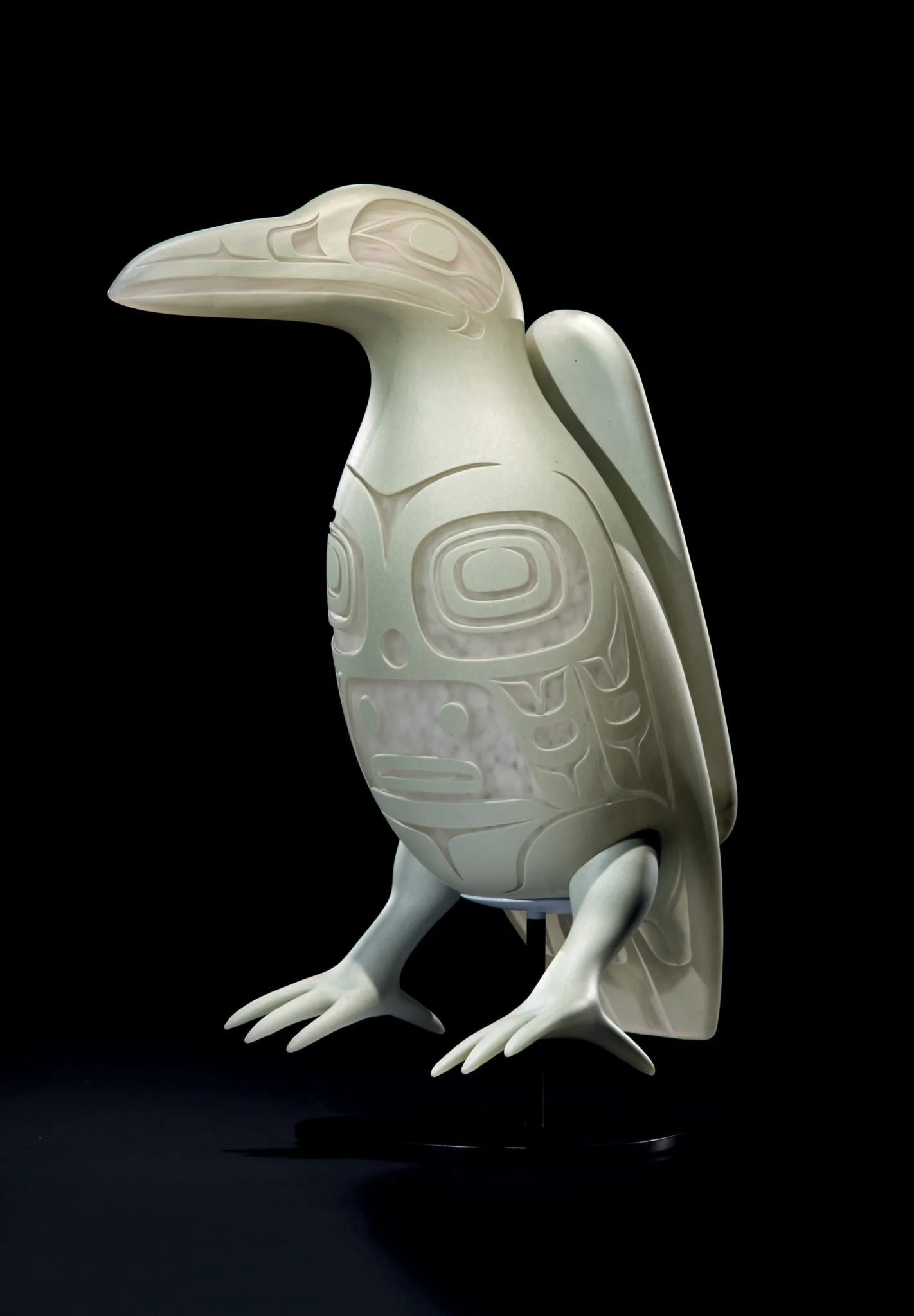

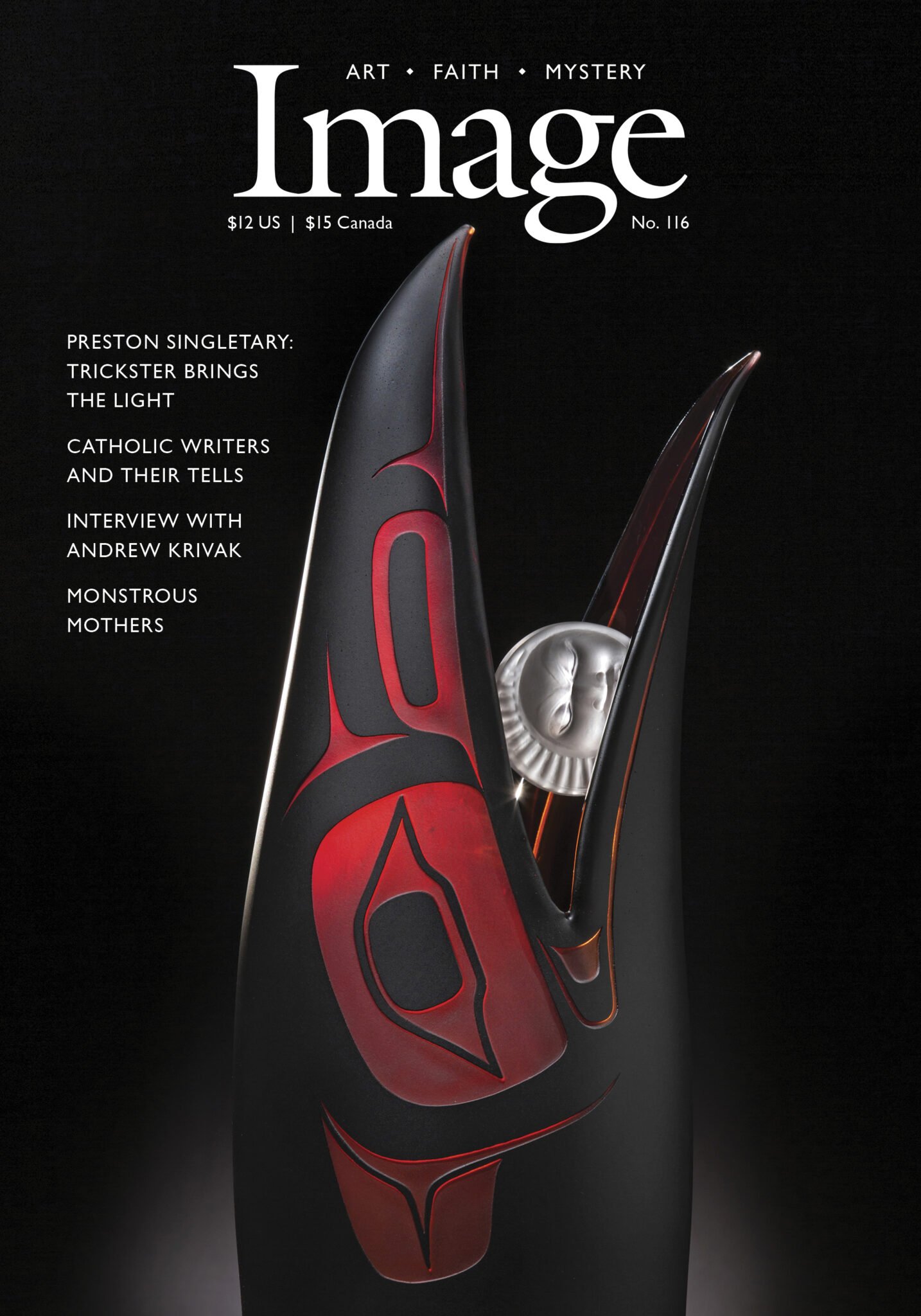

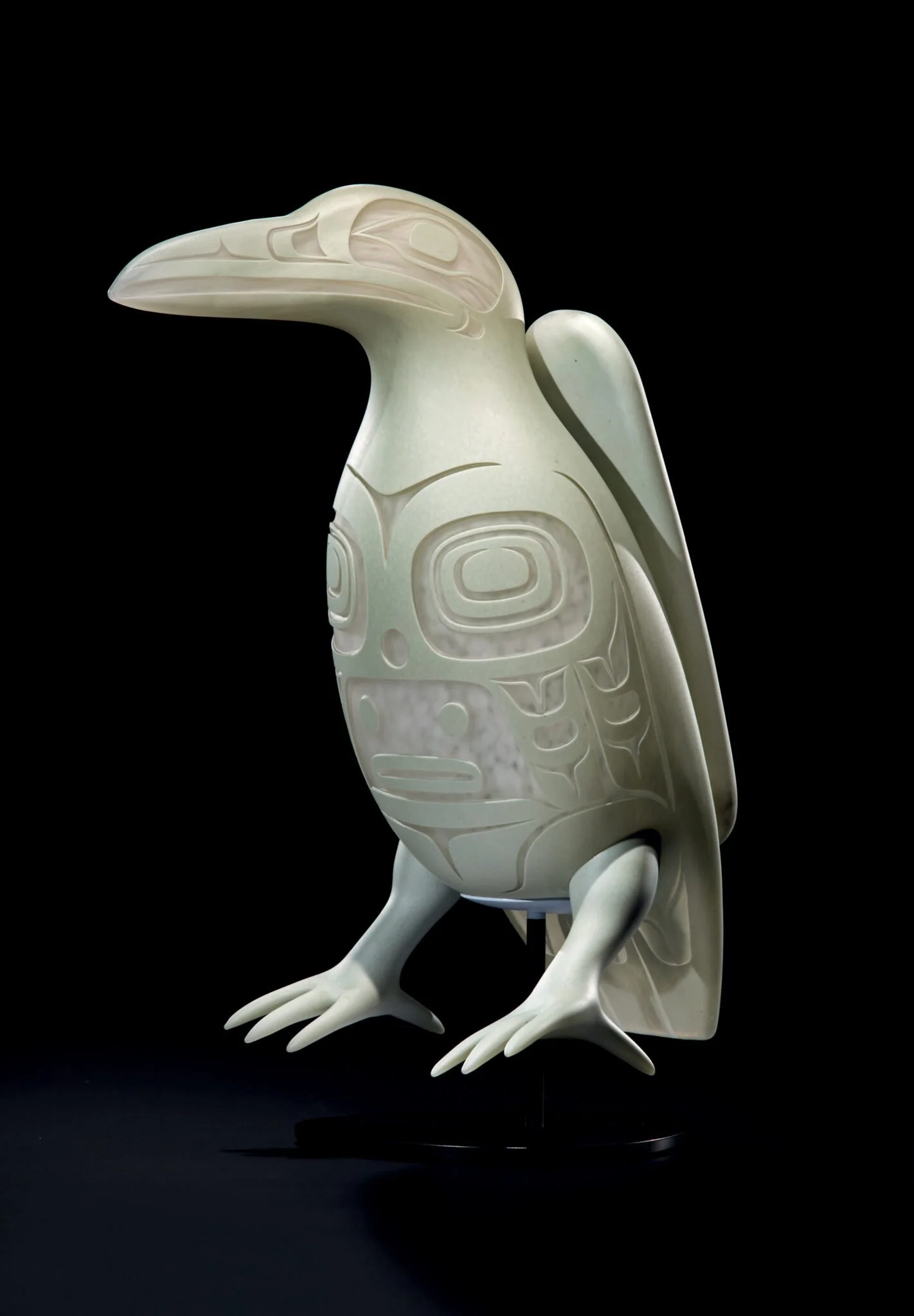

Raven Steals the Sun

Being a myth, the raven story can change its contours with each telling, but so long as certain events take place, it remains the raven cycle. It is still itself, you might say, in whatever form it takes.

Preston Singletary, Raven cover image

THE STORY GOES LIKE THIS:

A long time ago, the raven looked down from the sky and saw that the people of the world were living in darkness. The ball of light was kept hidden by a selfish old chief. So the raven turned itself into a spruce needle and floated on the river where the chief’s daughter came for water. She drank the spruce needle. She became pregnant and gave birth to a boy which was the raven in disguise. The baby cried and cried until the chief gave him the ball of light to play with. As soon as he had the light, the raven turned back into himself and carried the light into the sky. From then on, we no longer lived in darkness.

In many ways it really is the first story, a redemption narrative that also includes creation, incarnation, transubstantiation, and apocalypse, but it’s also the first version I heard of a story I would hear again many times.

The trickster-raven cycle is a kind of ur-story for tribes native to the Pacific Northwest, as ubiquitous among those groups as Noah’s ark is among some others. I first encountered it in junior high after my family moved to Washington State. It has traveled well beyond those bounds too, wandering in and out of other stories like some curious bird.

In poems, every word matters. In holy Scripture, the Word is what matters. But here, though the language and idiom may change with time and taste, the cycle is what matters. Being a myth, the raven story can change its contours with each telling, but so long as certain events take place, it remains the raven cycle. It is still itself, you might say, in whatever form it takes.

At the Tacoma Museum of Glass, when I saw Preston Singletary’s Raven and the Box of Daylight, a show that has since traveled to the National Museum of the American Indian and earned heaps of praise from critics, the feeling I had was of what E.T.A. Hoffmann would have called the uncanny: the familiar in the strange, or the strange in the familiar. It’s what we feel when looking at a stranger we think we recognize or hearing a remixed version of a song long cherished. I walked through the show enraptured, but with a constant nagging sense of déjà vu.

It wasn’t that the raven cycle so beautifully maps onto the Christian story of self-sacrifice and redemption—a mapping that is not, I think, a matter of cultural appropriation so much as of two cultures working toward and finding the same truth about the structure of the universe and the human heart. Rather, between those glass monoliths, the words of the familiar raven story were there, and they were different. Singletary had taken a story I’d cherished for twenty-some years, one that I’d memorized, and made it fresh.

Read the essay over at Image…

A Testament of Witness by David Lyle Jeffrey

Readers will be staggered at how much scholarship and good humor, how much formal dexterity and easy cadence, they find in these poems. A Testament of Witnesses is startling, aloft, and all of it singing an otherworldly glory.